In the first part of this two-part series covering QE in Canada, the emergency monetary policies taken by the BoC in response to the 2008 financial crisis were analyzed to show that many pundits are in fact incorrect to label the BoC bond purchases in 2008 as “debt monetization” or “QE”. Much of the material in this article necessarily draws upon concepts discussed in the first part of this series, and it is recommended that readers first acquaint themselves with the details of the previous article before continuing on.

Having now covered past unconventional monetary policy in Canada, specifically the response of the BoC to the Great Recession of 2008, this article will discuss the process of future QE in Canada in response to what is likely to be a severe downturn in the Canadian residential real estate market. It is often assumed that in the event of a significant financial crisis, the BoC will simply re-open the floodgates in a similar manner to 2008, aggressively purchasing private sector bonds in an effort to shore up asset prices, exert downwards pressure on interest rates, and inject liquidity into the economy in the form of newly created money.

However, as has already been shown in part 1 of this series, the BoC in reality did not unleash freshly-printed currency into the broad economy in 2008, pursuing instead a process of “sterilization” to trap excess currency in Federal Government deposit accounts held at the BoC. Given that the impending crisis in the Canadian real estate market is likely to be far more acute and disruptive than the financial crisis of 2008, the question remains as to whether or not the BoC will this time pursue a genuine policy of QE resulting in an increase in the money supply available as spendable currency to the general public. Just how likely is it, then, that the government is prepared this time around to unleash additional monetary stimulus into the economy in an effort to spark inflation expectations and combat the deflationary forces triggered by a large-scale collapse of the Canadian housing market? The answer, it seems, is “very likely”, for it is apparent that the Federal Government and BoC have already started the wheels turning on this very process.

It is generally unknown to casual market observers that in the period spanning 2011 to 2013 the BoC engaged in a renewed program of asset purchases which entailed purchasing large quantities of government bonds in exchange for what can effectively be coined as “printed money”. This is clearly visible on the asset side of the BoC’s balance sheet in Chart 1 below, which shows that shortly after their emergency asset purchase program was wound down following the 2008 financial crisis (shown as a sharp draw-down of the purple area in 2010), the BoC sharply ramped up their purchases of Federal Government Bonds (shown as a sharp increase in the light-blue area from 2011 to 2013).

But was the BoC engaging in some form of “stealth” QE as many pundits were at the time claiming? While it may indeed be true that the BoC’s specific role in the program was largely unheralded, the program itself was widely publicized as part of the Federal Government’s relatively well-reported emergency “Prudential Liquidity Management Plan” (PLMP). This plan, enacted largely in response to the 2008 financial crisis, called for an emergency fund to the tune of approximately $20 billion to be held at the Bank of Canada on behalf of the Federal Government. The stated purpose of this fund was to provide short term liquidity to the government in the event that normal lending channels were to seize up and access to standard funding markets became disrupted or delayed.

The point that critics were making at the time, however, was that instead of going straight to the debt market or tax base to fund their $20 billion contingency fund, the Federal Government instead turned to the BoC to monetize new bond issuances. The BoC subsequently purchased approximately $20 billion in new government bonds between 2011 and 2013 and credited the Federal Government’s account at the BoC with this newly-created money. In a similar manner to the way the BoC purchased huge quantities of public and private debt securities in response to the Great Recession with little inflationary impact on the economy (see part 1 of this series), the Federal Government and the BoC similarly “sterilized” these bond purchases by depositing the newly “printed” money into Government accounts with the BoC.

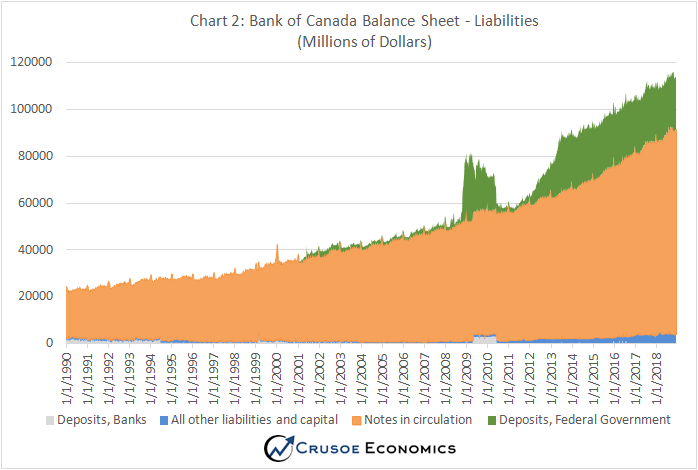

Contrary to the claims of many analysts at the time, the asset purchases undertaken as part of PLMP were not immediately inflationary since it did not result directly in circulating money being added to the public sphere. A graph of the BoC’s liabilities in Chart 2 illustrates this clearly, as it was in fact the Federal Government deposits (the green area) that dramatically increased commensurately with the BoC bond purchases in 2011-2013, and not bank deposits held at the BoC (the grey area) as would otherwise be expected if new money had in fact escaped into the broad economy.

What follows from the above discussion is that the BoC has in fact already “monetized” government debt to the tune of $20 billion which is currently sitting in Federal Government deposit accounts at the BoC. As long as the money remains trapped in the Federal Government’s account with an implied guarantee that it not be spent, the “debt monetization” can effectively be deemed as “sterilized” and the operation considered more or less benign. In this instance, and at the risk of splitting hairs, it is technically incorrect to claim that the BoC engaged in QE from 2011 to 2013 since no new money was in fact injected into the public domain. But this money is, however, most definitely available for future use. What we effectively have is a situation where the helicopter has already been loaded, but the money has yet to be pushed over the side.

Of course, when the next financial crisis rolls around, it is very likely that the Federal Government will resort to fiscal stimulus of some nature at which point the $20 billion emergency fund held at the BoC may potentially come into play. Does this mean the government will necessarily fund emergency spending with the proceeds from the 2011-2013 asset purchases? No, but it certainly does give the government the option to do so without being subjected to the negative criticism that comes along with monetizing debt in the throes of a full-blown financial panic. Due to the PLMP, the Federal Government now has at its disposal the full means to provide additional fiscal stimulus without resorting to either new debt issuance or further debt monetization on the part of the BoC. They need merely to claim that emergency spending is being funded through their “contingency reserve” or some other politically expedient catch-phrase in order to placate the general public, which will no doubt sound infinitely more reassuring to markets than announcing a Canadian version of quantitative easing.

The implication of the government spending down the $20 billion PLMP fund is obviously inflationary, but it should be kept in mind that this fund will likely only be accessed in an environment where deflation or disinflation is the primary concern. If money supply growth is already decelerating while the credit markets are at the same time seizing up, worrying about deposit money escaping into the public money supply is likely to be the least of the government’s concerns. Rather, in such a scenario it is highly likely that the BoC will be more than happy to stoke inflationary concerns in order to fight deflation, reduce the demand for money, and entice “hoarders” to release their cash stockpiles into the broad economy.

Of course, it should be kept in mind that the BoC can always monetize purchases of government bonds or any other private debt security at any time and in unlimited amounts if it so desires. In the event that additional QE is required on top of the $20 billion already supplied by the BoC, it should be expected that the funds will simply be printed into existence to fund the purchase of new debt issuances, whether sterilized or not. If the Federal Government requires new funds that it can’t access in the private debt markets, Canadians can rest assured that the BoC will most certainly step up to the plate in its official capacity as lender of last resort.

It should be noted that in 2008 the BoC engaged in sterilized asset purchases in order to drive down rates on bonds, support asset prices, and add liquidity to the overall financial system. These asset purchases, however, were only intended to be held on a short-term basis to provide liquidity to financial institutions and were always meant to be unwound once the crisis had eventually been resolved. The PLMP program, on the other hand, involves purchasing Government of Canada bonds on a much longer-term basis and is far closer to genuine QE than anything we have ever seen yet in Canada to date.

If the Federal Government and BoC are to be taken at face value, then this fund constitutes merely an emergency facility available to be drawn down under dire circumstances when market funding is in limited supply. However, given that the BoC is effectively able to monetize government debt at any time it deems fit regardless of general market conditions, it bears asking the question as to whether the BoC is instead simply testing the waters for an expanded role of this facility in preparation for the next big downturn in the Canadian real estate market.