Based on virtually every popular valuation measure currently in use, stocks today are expensive relative to the past. A lot of people have used this fact to make the case that equity markets are on the verge of a massive downturn, arguing that you’d best take your money off the table right now while the going is good. Of course, they could very well be right, but making the rather extreme call to sell all of your equities and wait in cash until the downturn eventually materializes requires a high degree of confidence in your valuation call. But is it really confidence, or merely hubris? I’m not sure – it’s a fine line. It’s one thing to look at the current high stock market capitalization-to-GDP ratio and plan for a future with lower equity returns. It’s quite another to sit patiently on the sidelines and risk missing out on a face-ripping bull market while everyone around you is making money hand over fist.

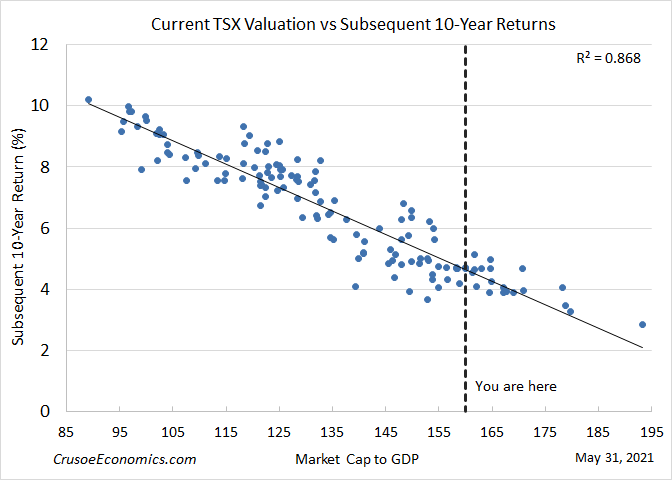

The thing is, being expensive doesn’t mean being overvalued per se. Sometimes something gets expensive because ownership preferences simply change in its favor, and what seems expensive today will seem cheap a year from now. The problem is that it isn’t possible to know exactly how investor preferences to own stocks will change over the years and in which direction the needle will move. For this reason, it can often make sense to simply extrapolate that the average valuation of the past will tend to be the average valuation of the future. In my own equity forecasts of Canadian stocks, for example, I assume that what people are generally willing to pay for stocks in 10-years’ time will be roughly what they’ve been willing to pay for it, on average, over the last 20 years. And indeed, there’s a strong correlation between current valuations and future returns. Here’s a graph of this correlation for the TSX.

Seems pretty convincing, doesn’t it? Lower returns are associated with higher equity valuations, so it stands to reason that at some point valuations could feasibly become so stretched to the upside as to virtually guarantee negative inflation-adjusted returns on a forward-going basis. But if you think about this critically, you’ll probably eventually ask why exactly I’m only using about 20 years of data in the correlation analysis? Well, the reason is simple – over the last 20 years, TSX stock market capitalization has maintained a fairly predictable relationship with Canadian nominal GDP. End of story.

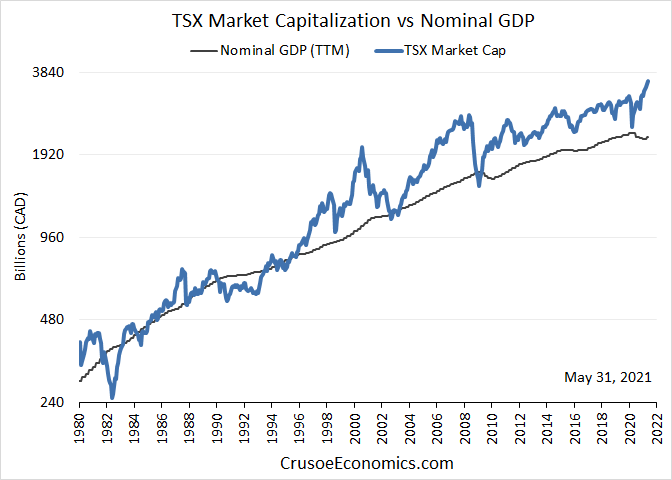

Take a look at the following graph. You’ll notice that since the mid 90’s, the market cap of the TSX has tended to trade above GDP for the most part, often getting ahead of GDP by a significant amount before occasionally falling back to roughly the same level of GDP near market bottoms.

This relationship, however, hasn’t always existed. If you now look at the period from 1980 to about 1995, you’ll see a 15 year period where the TSX market cap has generally tended to trade at about the same level as nominal GDP. This is starkly different from the period from 1995-2021 where the value of nominal GDP has tended to serve as a floor to the market cap of the TSX. During this more recent period, Canadian stock market capitalization has almost always traded above nominal GDP, with any pull-back towards GDP being a veritable gift for those looking to increase equity exposure.

Obviously, however, this relationship is only knowable in hindsight. We can see today that over the last 20 stocks have almost always traded above GDP, while falling below nominal GDP only occasionally. But an investor would certainly not have known this in the mid-90’s. To an investor in 1995 using the past 15 years as a baseline, virtually the entire period from 1995-2021 would have been classified as an overvalued market. Someone choosing to sit in cash in 1995 waiting until stocks were significantly discounted based on the valuations of the past 15 years would likely still be waiting to get in the market today. The fact is that over the last 20 years, Canadian stocks have simply become more expensive relative to the past. Investors simply want to hold them despite their higher prices. Why? Perhaps this is due to the low interest environment following the dot-com bubble in which investors were given the incentive to pay higher prices for equities given the low returns offered by cash and other safe assets. Whatever the reason, investors have simply become more willing to pay higher prices for stocks today than they were in the 80’s and early-90’s, but you would have never known that sitting hunkered down in cash in 1995.

And what about today? The TSX market cap-to-GDP ratio is high on a historical basis. Does this mean one shouldn’t buy equities? What’s the point of making forecasts, after all, if they aren’t going to help you align your equity allocations with expected returns? My answer: equity-market forecasts definitely should be used to baseline your return expectations, but you need to temper your faith in them. After all, it’s helpful to know that you’re likely going to get a sub-5% equity return over the next 10 years rather than the historical long-term return of 10% for the purpose of financial planning. But that doesn’t mean it’s written in stone. There’s no reason that future TSX valuations have to revert to the average valuations of the last 20 years. Just like there’s no reason that valuations over the last 20 years needed to revert back to the average valuation from 1980-1995.

It’s not inconsistent to forecast future 10-year equity returns delivering about 2% a year after inflation but still being invested in stocks. Given a negative real return in cash and bonds, equities perhaps aren’t the raw deal they’re being made out to be. And the bottom line is that valuations do change over time. They’re not static. Markets change, and so do investors. I’m certainly willing to concede that current valuations don’t necessarily need to mean revert to the average valuations of the last 20 years. Maybe they stay right where they are, or even increase and provide a tailwind to future returns. Who knows? Not you, and certainly not me. This is why you need to be cautious of overzealous bear forecasts based on the assumption of mean reverting valuations, lest you find yourself sitting in 100% cash during a barn-burning equity bull market.

This isn’t to say that the bears are wrong, or that I don’t think markets are over-ripe and set for some sort of correction. I can certainly see the argument that markets are getting ahead of themselves – I actually tend to lean with the bears on this one. But I also think that it’s possible that average valuations may simply be permanently higher going forward, and I’m not so confident in my model to discount this fact entirely. So are stocks expensive? Yes. Should you own them anyways? Probably.