As central banks increasingly turn to Negative Interest Rate Policies (NIRP) in an effort to jump start global growth, investors have been quick to deride this repressive practice as little more than a glorified tax on savers. Yet negative interest rates are hardly something new. Policy-makers have in fact been surreptitiously eroding the value of savings for years through the implementation of negative “real” interest rates, a process they have successfully been executing for the better part of two decades.

The real interest rate, of course, is simply the prevailing market interest rate minus the rate of inflation. If today’s savers earn 1% on bank deposits with inflation running at 2%, the real interest rate is calculated as -1%. While savers may superficially believe they are receiving a positive interest rate on their deposits, their real purchasing power is in fact being reduced at a rate of 1% per year as general prices rise at an even faster pace. Likewise, if the adoption of NIRP were to suddenly reduce the interest paid on deposits to -1% with inflation remaining at 2%, the real interest rate would correspondingly decline to -3%.

We can see from the above scenario that the implementation of NIRP served merely to reduce the real interest rate from -1% to -3%. Seen in this light, NIRP is simply a gradual extension of the current trend towards increasingly negative “real” interest rates. The challenge faced by investors over NIRP, then, turns out to be merely part and parcel of the same old existing challenge of the last twenty years. Namely, how do investors escape negative real interest rates more generally for the liquid portion of their retirement savings? Fortunately, there is one asset class that tends to be inversely correlated with negative real interest rates and, as readers will undoubtedly guess from the title of this article, that asset is gold.

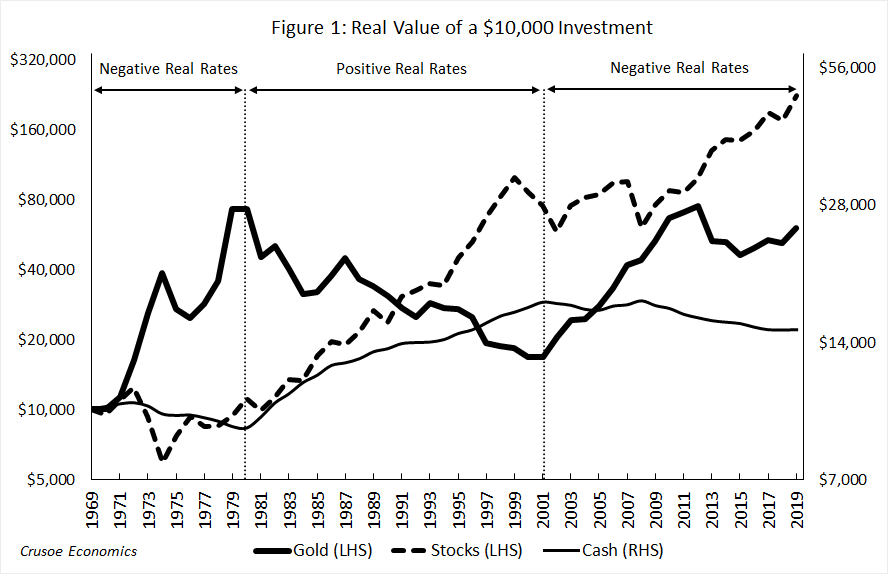

As was previously explained in the article Debunking Gold (see the October 2018 edition of Canadian MoneySaver), gold tends to perform well when the public desires to save due to growing economic uncertainty but is unable to do so in the official medium of exchange. Said another way, gold becomes the investment of choice when savers are increasingly unwilling to hedge against declining economic confidence by saving in perpetually-debased dollars. Figure 1 illustrates this relationship by charting the real (inflation-adjusted) value of a $10,000 investment in gold, stocks, and cash (represented by Treasury Bills) for the period 1969-2019.

Importantly, the inflation-adjusted value of cash shown in Figure 1 delineates long term trends in real interest rates, with declining real values of cash being indicative of a negative real interest rate environment, and a rising real value of cash representing a period of positive real interest rates. The performance of stocks illustrates secular trends in economic confidence, with long periods of sideways movement denoting periods of economic stagnation and a long-term upwards trending stock market indicating periods of robust economic growth and confidence.

It should be obvious from Figure 1 that gold tends to perform extremely well during periods of negative real interest rates and declining economic confidence, while suffering large losses during periods of positive real interest rates and increasing economic confidence. Both the 1970’s and the period from 2001-2012 represent periods of negative real interest rates and economic stagnation during which gold delivered outsized real returns and cash performed especially poorly once adjusted for inflation. Conversely, both the 1980’s and 1990’s represent periods of consistently positive real interest rates and strong economic growth where gold endured a painful and punishing bear market in the face of especially strong returns for holders of cash.

From a historical perspective, the 1970’s was a period where the benefit of high interest rates was more than offset by even higher inflation, resulting in investors flocking to gold as an alternative form of safe “liquidity” in which to store their savings. The current era of negative real rates, on the other hand, is one characterized by low inflation. Yet it is also a period characterized by extremely low interest rates which have generally failed to surpass the rate of inflation for the majority of the last two decades. As today’s negative real interest rate environment increases the cost of holding one’s savings in cash, it simultaneously makes storing wealth in a zero-yielding asset like gold increasingly appealing. This is why, despite the low-inflation environment that began in the late-90’s, gold spent more than a decade immersed in a secular bull market from 2001-2012.

Of course, all of this begs the question as to why, if one expects negative real interest rates to continue for the foreseeable future, do investors not simply trade out their cash positions for gold in order to maintain the purchasing power of their savings? As we can see from Figure 1, the answer to this question lies in gold’s gut-wrenching volatility. While gold may indeed be inversely correlated with real interest rates, this correlation is neither linear nor predictable in the short term. Although gold tends to have an upwards bias during periods of negative real rates and a downwards bias during periods of positive real rates, short-term price movements in gold are also influenced by other factors (such as economic confidence) that can cause stomach-churning swings in the gold price from one year to the next.

During the roaring gold bull market of the 1970’s, for example, nominal gold prices suffered a punishing near-30% decline before subsequently breaking out to new highs only a few years later. Conversely, gold’s brutal bear market during the 1980’s and 1990’s was interrupted by a 57% gain between 1985 and 1987, only to be followed by a renewed decline over the subsequent 14 years that saw gold lose a staggering 43% of its value. With an economic climate of negative real interest rates becoming increasingly entrenched from 2001 onwards, many observers expected gold to begin an uninterrupted bull market as the purchasing power of savings was gradually eroded due to inflation. Yet even with the tail-wind of negative interest rates at its back, increasing stock market strength and renewed economic confidence reduced the demand for safe liquidity beginning in 2013, punishing gold investors with a loss of approximately 37% from 2013-2015.

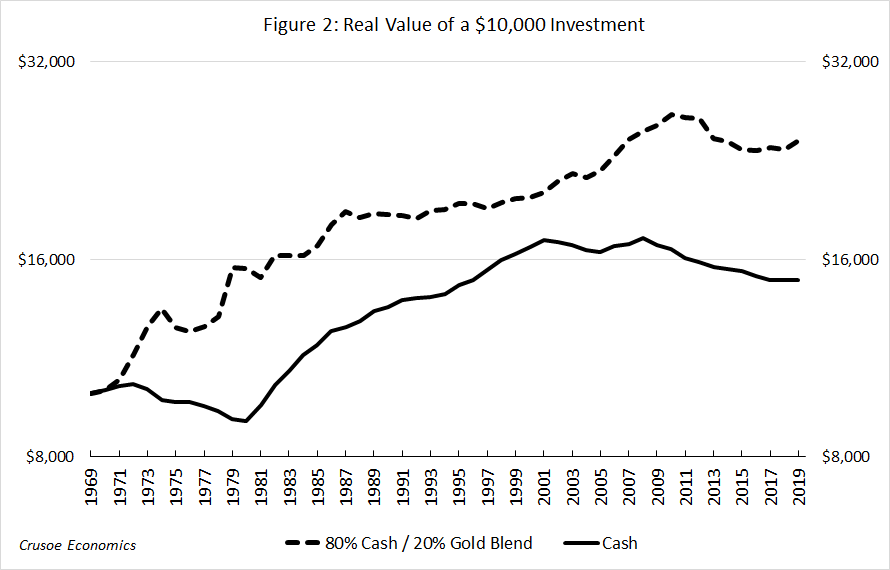

Importantly for savers, holding gold is hardly an all-or-nothing proposition. Even swapping out a small portion of one’s cash allocation for gold can result in significant protection against the loss of purchasing power while also minimizing gold’s extreme volatility. Figure 2 illustrates the real returns of a $10,000 investment in a portfolio of 100% cash versus one containing a blend of 80% cash and 20% gold. While we can see that the cash/gold portfolio does tend to moderately increase overall volatility, it also serves to preserve the purchasing power of one’s valuable liquidity over time.

While the inflationary 1970’s was certainly a poor decade for a pure cash portfolio, the cash/gold blend not only preserved real wealth, but actually managed to increase it. These same properties of capital preservation are also evident in the negative real interest rate environment from 2001-present, where a relatively small allocation to gold served to increase the real value of an investor’s liquidity balance over time. From a practical perspective, the volatility inherent in holding one’s liquidity in gold can easily be mitigated through position size limits and basic diversification. If an investor, for example, is content to hold 10% of their overall portfolio in cash, substituting this 10% pure cash position for a 10% cash/gold “liquidity” blend as shown in Figure 2 would amount to a total gold allocation of only 2% of the entire portfolio value. This is hardly the stuff of extremes.

Of course, we can already hear the howls of protests denouncing the idea that gold serves as some sort of liquidity alternative to cash. After all, so the critics argue, gold may be many things, but it isn’t money. While it is true that for the most part gold cannot be readily exchanged directly for goods and services, gold is no less money to a Canadian investor than, say, US dollars or Swiss francs. A person living in Canada may not actually be able to “spend” their gold at the supermarket, but nor can they spend any other foreign currency either. To purchase goods at the local grocery store people must first convert their US dollars or Swiss francs into Canadian dollars, but nobody would suggest that US dollars and Swiss Francs aren’t actually money.

In many ways, then, gold functions as the foreign exchange component of an investor’s highly liquid assets. In fact, given that the current negative interest rate environment shows no signs of letting up anytime soon, gold will likely serve as the premier foreign exchange asset during the next large-scale economic downturn. After all, if gold really is just another type of foreign currency, we would do well to remember that one of the primary drivers of exchange rates is the interest rate differential between two competing currencies. While it is true that gold doesn’t pay interest, at least it doesn’t pay negative interest. And in a world where the trend appears to be moving increasingly towards NIRP, gold may ultimately end up being the highest yielding currency of the lot.

Note: A modified version of this article was published in the February 2020 edition of Canadian MoneySaver magazine. It is re-published here with permission. To read the complete version, click here