Financial pundits are often quick to chide Canadian investors over excessive home-country bias and a perceived lack of international diversification when it comes to their equity investments. The Canadian stock market, after all, is a relatively small share of global markets, and holding 100% of one’s equity exposure domestically fails to take advantage of proper portfolio diversification, or so the argument goes.

The purpose of this article isn’t to question the long-standing tenants of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) per se, but merely to prod Canadian investors to question some of their unchallenged assumptions regarding the popular wisdom that international diversification is unequivocally beneficial. While it’s possible that in some cases international diversification may help slightly at the margins (although even this is debatable), it’s hardly the great risk-diversifier many financial advisors would have you believe.

Canadian investors, of course, can be forgiven for their lack of enthusiasm for international diversification, particularly when global stocks have effectively tracked domestic markets more or less in lock-step over the last several years. The following chart shows the iShares ETF for the Canadian stock market (XIC) overlaid with the ETF for the All Country World Index (XAW), which is unhedged to the Canadian Dollar. Domestic investors looking for global equity diversification over the last 4 years would clearly have been sorely disappointed.

Of course, there are many objections to this kind of cursory comparison with international markets. The first is that the look-back period of 4 years is simply not long enough. In the very long run, so the argument goes, international markets provide much higher levels of diversification than the last 4 years would suggest. But is this really helpful to everyday investors who will be investing their retirement savings over, say, the next 10 years? The following chart shows the 10-year rolling correlations between Canadian and international stocks (priced in CAD) since 1970. The horizontal axis shows the end year of each rolling 10-year period (for example, 2018 refers to the period from 2009-2018), while the vertical axis plots the correlation coefficient between Canadian and international stocks.

The first thing readers will note from the graph above is that the 10-year rolling correlations between Canadian and international stocks going back to 1970 have been positive one hundred percent of the time. A positive correlation means that both markets tend to rise or fall at the same time, which isn’t entirely unexpected between two markets that have generally trended upwards throughout history. What is interesting is just how volatile these correlations are, ranging from a peak positive correlation of 0.91 to a much lower positive correlation extreme of 0.28.

The frequent periods showing high positive correlations in the graph above illustrate that the diversification benefits of international stocks tend to periodically evaporate depending on which decade an investor happens to be living through at any given moment. As is obvious from the large swings in the chart above, advising someone to invest based on an average correlation is akin to dressing for the average temperature and not expecting to get frostbitten during the winter. International diversification from 1991-2000 probably did a Canadian investor a lot of good. Global diversification from 2001-2010 probably not so much.

Of course, the point of good asset allocation is that on the way up, one asset will zig while the other zags, which tends to reduce risk. While the academic definition of risk is volatility, no real world investor actually perceives risk in this manner. Any investors who has ever been through any sizeable market correction knows that it is really draw-downs that matter to investors, not whether their portfolio happens to be up 2% when the historical average return is 10%. From that perspective, what an investor really cares about with respect to risk is draw-down size, draw-down duration, and draw-down frequency.

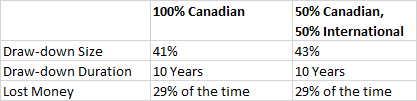

The table below shows the historical risk profile of a portfolio containing 100% Canadian stocks versus one that contains 50% Canadian and 50% international equity since 1970. As we can see, real-world risk measures of max draw-down size, max draw-down duration, and draw-down frequency are nearly identical, with the “diversified” version of the portfolio incurring a max real (inflation-adjusted) draw-down of 43%. Readers would do well to note that this max draw-down of 43% was actually higher than the max draw-down of 41% for the pure Canadian equity portfolio. If the point of international diversification is to reduce portfolio risk, the evidence would seem to cast significant doubt on the ability of global equity to hedge stock market draw-downs, at least from a Canadian perspective.

And yet the above chart still does not fully account for all the risks a Canadian investor will face from outsized exposure to international equity. Domestic Canadian investors are repeatedly told to internationally diversify their equity exposure, but they are virtually never told to do this for their fixed income component. But if bonds are purchased to hedge your equity risk, Canadian investors in international equity have now decoupled their stocks from their downside equity hedge.

If it is true that bonds should rise when stocks fall as investors pile into safe assets, a Canadian investor in global stocks may not see the same risk mitigation from their domestic bond portfolio when their international equity slice takes a beating. After all, domestic financial conditions such as interest rates respond to domestic inflation and business conditions, not necessarily international ones. Investors who are largely out of Canadian equity in favor of global stocks are potentially surrendering the protective utility of their bond allocations.

All this is to say that Canadian investors have just increased their international “event risk”, which is the risk that an acute crisis that isn’t Canadian born causes deep-draw downs in their portfolio at the same time their primary equity hedge fails. Of course, one could say that there is an even greater “event risk” that Canadian equity markets crash in isolation, but a proper portfolio with domestic bonds, domestic cash, and global assets like gold will already have hedged against the risk of both domestic market losses and Canadian dollar losses. In other words, Canadian investors holding a broadly diversified portfolio of non-equity assets are paying an opportunity cost to hedge against the domestic Canadian economy. If you largely replace your Canadian equity exposure with international equity, then what in the world are you paying for?

All this is well and good, the critics will say, but the future isn’t certain. If you have the ability to diversify internationally, why shouldn’t you, especially given that Canada is a commodity producing nation that is attached at the hip to the ebbs and flows of raw material prices. Since everyone knows that as commodities go, so too goes the Canadian stock market, isn’t international diversification simply a prudent way for domestic investors to hedge against commodity price risk? While this might be true in some cases, the narrative that Canadian markets move in lock-step with commodity prices is a false one, or at least it has been over the last 10 years.

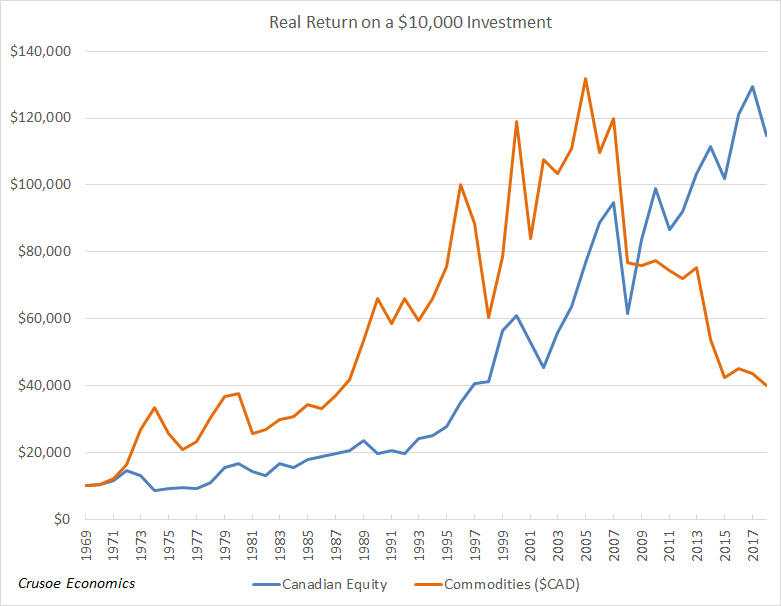

As the chart below shows, the fallout from the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 caused both Canadian stocks and commodities to move sharply lower in unison (in conjunction with most global equity markets). However, the next 10 years saw a large rebound in domestic stocks (as well as international stocks), while commodity prices continued to move sideways before once again crashing in 2014. In other words, falling commodity prices have not historically always led to falling Canadian equity prices, just as any future commodity bull market will not necessarily lead to a strong advance in Canadian stocks.

Even if international diversification isn’t the great diversifier that portfolio management practitioners would have us believe, given the ease of purchasing international exposure via ETFs, isn’t owning some global equity prudent in the off chance that historical correlations are completely turned on their heads in the future? Of course, trying to reduce risk is never a bad idea, but like everything in investing, this depends on the cost. While MERs on global ETFs like XAW (mentioned above) are certainly higher than domestic stock ETFs like XIC (also mentioned above), the real issue comes down to the fact that most Canadian investors tend to hold the bulk of their investments in RRSPs and TFSAs.

From a tax perspective, ETFs holding foreign stocks subject Canadians to a foreign withholding tax on dividends, meaning that distributions paid out to investors by these ETFs have already been reduced by as much as 30%. Canadian investors are sometimes able to recover these foreign withholding taxes at year end via tax credits, but these costs are completely non-recoverable to an investor holding Canadian listed ETFs within an RRSP or TFSA. Foreign withholding taxes are currently 30% of distributions on US stocks and average approximately 12% of distributions for international stocks (according to BlackRock). The implications of this are that foreign withholding taxes, in conjunction with higher MERs for ETFs tracking global stocks, constitute a non-trivial added cost for Canadians attempting to invest in international equities. Furthermore, if dividends happen to become an even greater proportion of total stock market returns going forward, the drag on investment returns from withholding taxes will tend to increase over time as well.

On the other hand, there are certainly ways to skirt around or mitigate withholding taxes by purchasing individual international securities directly or by purchasing US listed ETFs instead of Canadian ones, but all of this adds complexity. And while increased complexity isn’t a financial cost, it’s a cost nonetheless with a non-trivial impact on how investors perceive and manage their investments. This is all to say that if there’s no clear advantage to increasing cost or complexity, then why do it at all?

Of course, we can already hear the chorus of protests pointing out that this is a classic example of allowing the “tax tail” to wag the “investment dog”. Hardly. Rather, this is more the case of allowing the “risk-adjusted return dog” to wag the “frictional-cost tail”. Critics of this approach will tell you that international diversification is a free lunch that serves to slightly increase returns, but net of costs is this really true? They will also point to the fact that in the long run, international diversification supposedly decreases risk. Perhaps it decreases volatility, but in terms of decreasing the real risk that average people actually care about (ie. draw-down pain), the evidence is far from convincing.

The reality is that during large scale stock market draw-downs, it likely won’t make one iota of difference whether your slice of equity is globally diversified or not. In fact, most investors likely have a false sense of security in their investments due to their advisors constantly pushing international diversification as a valid risk-mitigation tool. The truth is that in market panics, stock investors will be hammered with large scale draw-downs regardless of their international equity exposure. Investors simply need different assets to diversify against stock market risk, not merely different types of the same asset.

Critics of Canadian home-bias undoubtedly have good intentions, but they would do well to instead focus their attention on things that actually make a meaningful difference to average investors, such as structurally diversifying portfolios in order to minimize draw-downs across economic regimes. Certainly, global diversification may increase returns at the margins and help a bit on the volatility front, but it also serves to increase cost and complexity, does little to help investors stay the course during market draw-downs, and perhaps even decreases portfolio robustness against international “event risk”.

So once more, given the added cost of global equity exposure to Canadian investment portfolios for seemingly little benefit, I ask again, what’s the point of international diversification?